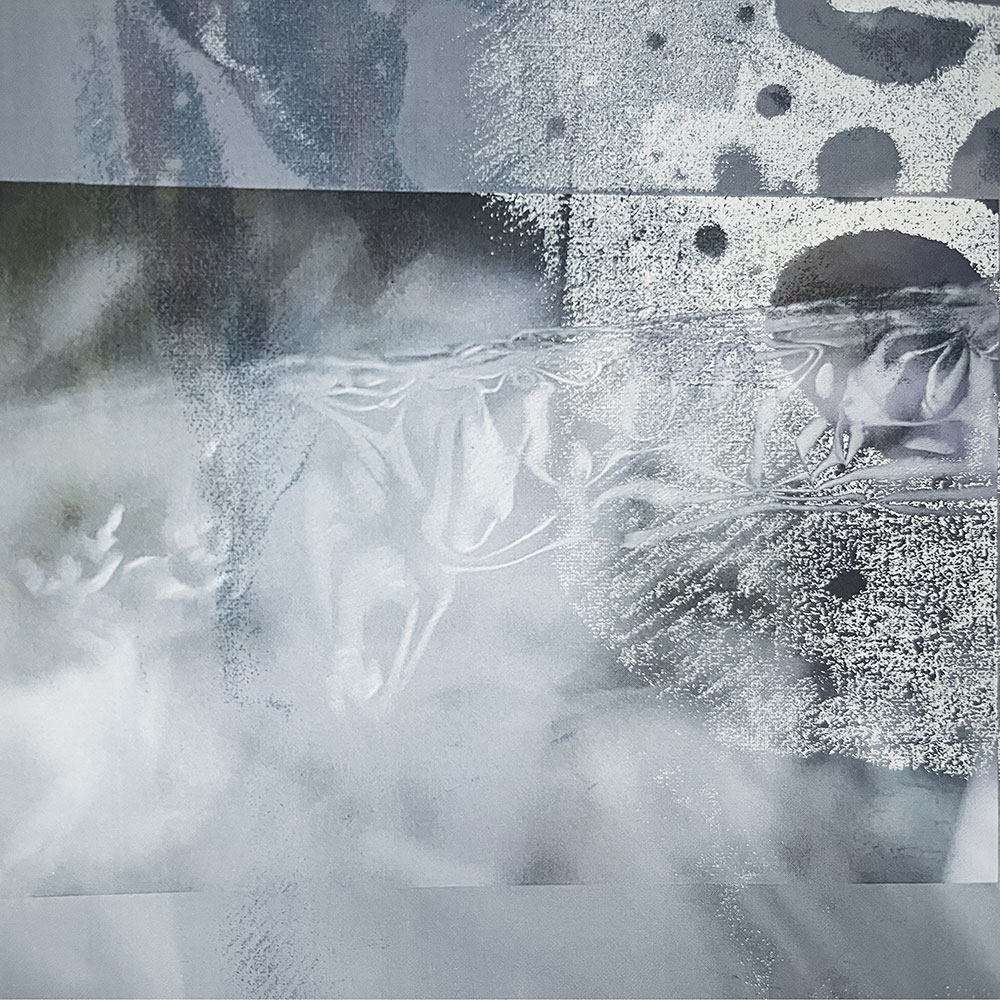

Everything in Its Right Place. You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet. Reconstructing a new order within chaotic multiple narratives and investigating the subtle space between void and reality, Junshu Gu’s work appears minimal and abstract, yet remains lithesome and precise.

Born: Shenyang, China

Now: London, United Kingdom

@ikuulikki | www.kuulikki.com

INTERVIEW

How did you transition from working in the media industry to visual arts?

This is a long story. I often describe myself using Deleuze’s concept of the “line of flight.” I used to be a film editor, focusing on international film festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, and Venice. Then, I coincidentally stepped into the music industry, progressing from a journalist to the content director of a music streaming platform like Spotify in China. Simultaneously, driven by my interest in contemporary art and proficiency in critical writing, I contributed art critiques to numerous media outlets.

Having had the privilege of engaging with world-renowned artists such as Cai Guo-Qiang, I gradually felt a desire for a more subjective expression beyond merely organising content. Consequently, I quit my job and pursued further studies at the Royal College of Art. My prior experience in the cultural scene has provided substantial support, allowing me to recognise the voice I wish to express. This awareness has also fuelled my willingness to embark on a second life as an artist.

Could you tell our readers about the concept that forms the foundation of your work? What themes do you explore in your art?

I have always been fascinated by the edge between chaos and order, reality and fiction. Chikamatsu Monzaemon, the renowned Japanese dramatist of the Edo period, has a theory called “Kyojitsu Himaku” (虚実皮膜), which posits that art exists in the subtle space between void and reality, separated by just a “skin membrane.” Therefore, my concerns repeatedly revolve around questions of pessoptimism, social anxiety, and the hidden initiative in chaos.

All my work is rooted in rhizome theory and draws from my 13 years of interdisciplinary culture-related media work experience and profound expertise. Borrowing from the vocabulary of New Wave film, the anti-novel, and minimal music, I strive to address the allegorical narrative potential that arises from the edge of chaos in the real world, aiming to examine the absence of the female flâneur and the glass ceiling for women in contemporary discourse.

Junshu, in your opinion, what is the role of women in art and life?

This question touches on several intricate issues. I do not wish to deliberately emphasise the importance of the role of the female, as it is an indisputable fact. I believe that on the stage of art and life, the most crucial aspect is for any individual or group to perform their role well within the grand narrative. Frankly, my initial creations did not explore within the framework of feminism. However, my awareness shifted when I encountered boundaries in the real world as a woman. It is at that moment that questions arise. It is akin to living in a healthy body where different parts do not have a strong sense of presence, and everything operates naturally. But when there is an issue, even something as minor as a cut on your finger, that part’s presence is immediately magnified. Encountering the glass ceiling in the workplace makes these limitations tangible, preventing women from fully playing the roles they deserve. This imbalance is what I, as an artist, now seek to express.

Tell us about your project “All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking, but…”, which has been presented at various events and received numerous awards.

The story begins in 2022, in Barcelona, where my phone was robbed by a man on a motorbike—an unfortunate but not uncommon incident. For a self-organized woman who prides herself on being a flâneur on solo trip, this experience dealt a blow to my self-perception and was considered a trauma. This prompted me to question the definition of the flâneur.

During my research, the unexpected happened. In early French, the feminine equivalent of flâneur was not a female flâneur, but an indoor lounge chair. The absence of women was not only present in the 19th century but persists in contemporary discourse. Two months later, I returned to Paris, the birthplace of the term. In the aura of Walter Benjamin, I filmed this moving image work. Through a non-linear narrative, following the rhythm of Virginia Woolf’s Street Haunting, the video shares thoughts on the coexistence of resilience and vulnerability. The title is a quote from Nietzsche, while the word “but” introduces a new line of questioning.

Which of your projects was the most challenging or difficult, but you are satisfied with the result? What was the audience’s reaction when you presented this work?

It is undoubtedly “I Hope This Finds You Well.” While the theme has consistently been centered around the anxieties of contemporary urban dwellers, the initial conception of the project and its eventual result diverged significantly. I was resolute in my idea that I required a balloon of my height as a symbol of anxiety. I experimented with various media, striving to convey the metamorphosis of anxiety, yet none proved entirely satisfactory.

Interestingly, when I first inflated the balloon in my apartment, this enormous object almost filled the entire living room, immediately evoking a sense of anxiety due to the stark spatial contrast. The balloon’s mirrored surface perpetually confronted me with my own reflection, making my presence inescapable. Ultimately, I decided to live with it, my anxiety, for a month and document the entire process. In a moment of epiphany, everything fell into place. As for the audience, if you are sincere enough, they will always be able to perceive it.

Your CV includes participation in numerous exhibitions. Which event do you consider the most significant in your career as an artist?

Throughout my relatively short artistic journey, each exhibition has held special significance for me, particularly as someone who transitioned from another field. If I had to choose one, it would be screening my moving image work alongside other Royal College of Art artists at Tate Modern Lates. During times of creative block, Tate Modern was the place I visited most often. Thus, transitioning from being an audience member to screening my work as an artist at Tate was a surreal experience. Although it was a small appearance within a larger event, this opportunity provided me with immense energy and reinforced my determination to pursue my future as an artist.

Additionally, having the chance to see my work on the big screen in Rich Mix Cinema through Shorts On Tap’s Body Of Work was profoundly significant for me, particularly given my past as a film journalist. This milestone reaffirmed the importance of my artistic endeavours.

What advice would you give to emerging artists or to your younger self at the start of your journey?

When you have made countless choices, if you have the opportunity to become an artist, maintaining your creative practice is ultimately the best and final choice; please persevere.

Similar to Deleuze’s rhizome theory, direction, speed, and even the outcome are not the key factors; the essential thing is to keep moving, and you will eventually find your own line of flight. I would like to conclude with a line from the film La Haine: “Jusqu’ici tout va bien. (So far, so good.)”