I sketch the thoughts we’re told to keep quiet and stretch them into rooms you can walk through. My work sits where old rituals meet new screens, turning hush-hush subjects into shared curiosity.

Born: Qom, Iran

Now: London, UK

@seyyedebrahimi | www.seyyedebrahimi.com

Critical Review

Seyyedebrahimi’s work is a compelling fusion of cultural introspection and technological innovation. By leveraging immersive media, he not only challenges societal norms but also creates spaces for personal and collective reflection. His ability to intertwine the ancient with the avant-garde positions him as a pioneering figure in contemporary immersive art.

Anna Ponomarenko, Editor

INTERVIEW

Your artistic journey began in a restrictive religious environment. How has this background influenced the themes and narratives in your immersive works?

Curiosity had a curfew when I was a kid. Every book was screened, music speakers were a no-go, and questions were condensed. All that filtering tuned my ear to whatever was missing—desire, doubt, raw emotion. Those missing pieces eventually became the raw material for my practice; instead of picturing hidden chapters in my head, I now sculpt them into walk-through spaces. Using hand-drawn textures, responsive light, and sound that breathes with the viewer, I give form to the gaps I once had to imagine. The moment someone steps in, the story is unfinished—they complete it by choosing where to pause, what to touch, when to turn away. In that exchange, the silence I grew up with finally starts speaking.

Your art often merges ancient cultural elements with futuristic technology. How do you balance these seemingly contrasting aspects to create cohesive experiences?

I still treat technology as a frame, not the picture. The groundwork is always something that carries weight—ink on paper, a scrap of folklore, a pattern lifted from old masonry—and only then do I ask which digital touch will stretch or illuminate that core. If the tech starts shouting louder than the story, I turn the volume down. Think of it as playing a classical melody on an electric guitar: the distortion’s a thrill, but the tune still has to sing.

I’m just as careful with interaction design. I avoid flashy, sci-fi gestures; instead, I lean into movements that feel so ordinary they’re almost invisible. Your gaze shifts the light, a slow breath thickens the soundscape, a curious step forward wakes a creature hiding in the dark. Viewers often don’t realise they’re “interacting” at all—that subtlety is the point. When the technology feels as natural as reaching for a door that’s already ajar, the story can slip under the skin without announcing itself.

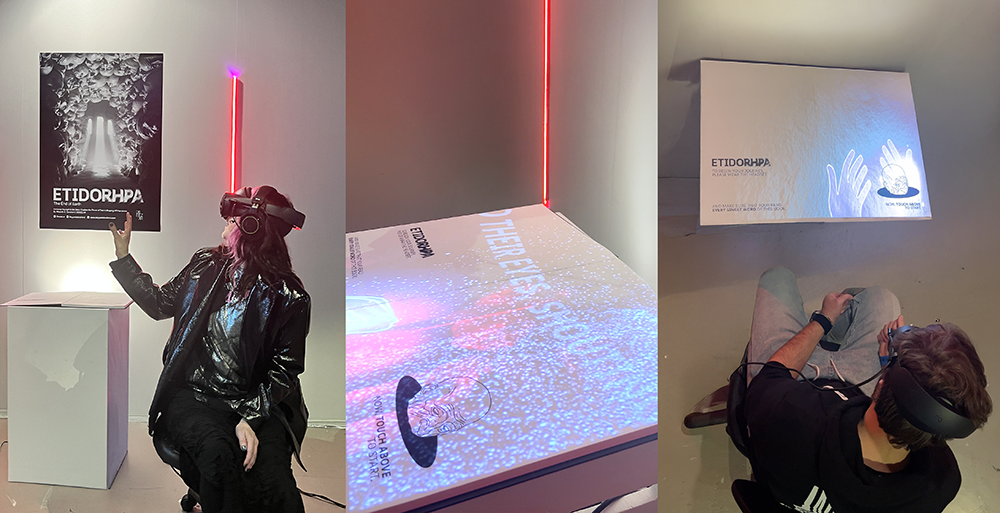

Projects like “Etidorhpa” and “Ooh La La!” have garnered critical acclaim. Can you discuss the conceptual development and technological integration in these works?

Both pieces started as questions. Etidorhpa began with memories of cramped mourning ceremonies where everyone recites yet no one truly speaks. I wanted to flip that tension—turn reading, the quietest of acts, into something that shakes the room. The solution was a book that “opens” into VR. Eye-tracking watches which words you linger on; each line you read unlocks sound cues, tilts the lighting, or sends a ripple through the corridor of mouth-less heads, so text stops being passive and becomes the action itself. Ooh La La! started with a different sort of hush: the awkward silence around adult pleasure. It started as: what happens if you remove the “sex” from “sex-toy”? Large, candy-bright objects in VR and mixed reality respond to touch, squeeze, and shake with melodic or game-like responses. The work exchanges secrets for shared pleasure by wrapping these once-hushed objects in humor, erasing stigma one laugh at a time. Interactions are designed to be low-friction so participants forget they’re using tech—curiosity does the work. The result is less about show than about letting people experience pleasure like any childhood toy, turning forbidden into a conversation starter.

Having exhibited in diverse cultural contexts—from Iran to the UK and the USA—how does audience reception vary across these regions?

Reactions shift with the cultural weather. In Iran, viewers read the subtext before the headline—they’re experts at spotting coded critique and often pull me aside to share quiet interpretations. In the U.S., audiences tend to lead with the tech: the first questions are about eye-tracking or the technology that makes 3D-printed parts responsive to touch; only after that do they circle back to the politics. UK responses are immediate and vocal—people often say what they’re feeling while still inside the headset, turning the gallery into a kind of live commentary. I’ve also showcased Ooh, La La!in the Netherlands, where viewers lean into playfulness—there’s less blush around taboo, so they dive straight into interaction and only later begin to unpack the deeper themes. Same work, four different entry points, each revealing something new about the piece—and about the people engaging with it.

Mostafa, what challenges have you faced in pushing the boundaries of immersive art, and how have you overcome them?

Pushing the boundaries of immersive art often means rethinking what’s been taken for granted. For me, one major shift was turning text—which is usually passive informative in immersive spaces—into something active, visual and central. In Etidorhpa, for example, the act of reading doesn’t just deliver content; it drives the entire environment. That idea can grow beyond VR too—into websites, installations, even physical publishing.

Of course, there are the usual headaches: funding, hardware access, and long render queues. I didn’t come from a tech background—I couldn’t code—but AI tools helped me bridge that gap and build prototypes on my own terms. One of the tougher barriers has been convincing curators to take immersive work seriously in gallery settings. It’s still a challenge, but the landscape is changing—there’s more openness now than even a year ago.

My method has always been “analogue first”: get the emotional beat right on paper, then move into low-fi VR to feel out the space before polishing it with high-end tools. That way, the soul of the piece doesn’t get lost behind layers of software.

Looking ahead, are there specific themes or technologies you’re eager to explore in your upcoming projects?

Looking ahead, I’m working on a project that involves interviewing people who lost their eyes during the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement in Iran. The goal is to create an immersive storytelling experience that doesn’t just tell their stories—but allows people to feel the absence of the gaze, the silence that follows such a loss.

On the technical side, I’m currently exploring Gaussian splatting, which opens up a new way of thinking about interactive photography. I’m using it to scan real Iranian environments and merge them with personal and political narratives from the movement. The result, I hope, will be a poetic yet hyper-real encounter—one where viewers move through both space and emotion, experiencing the tension of lives shaped by restriction and resistance.

What advice would you offer to emerging artists interested in combining traditional storytelling with immersive technologies?

Treat immersive tech as a new lens, not a new alphabet. Humanity’s been telling stories for millennia—myths, epic poems, shadow plays—and most of that toolbox is still wide-open territory in VR and AR. So start small: stage your idea with paper maquettes, flashlight “spotlights,” or a friend reading dialogue before you touch a line of code. If the scene moves you in that lo-fi form, it will sing once you add tech.

Let the story dictate which sensors or shaders you need, not the other way around. And never abandon the tactile stuff—sketching, sculpting, handwriting, drawing.

Those analogue instincts become your compass when the headset goes on and the pixels start crowding for attention.